By Jeff Pepper

Originally published February 4, 2008

A short time back, 2719 Hyperion reader Steve Pierson shared with me photographs he had taken on a recent visit to Kansas City, Missouri. Walt Disney lived in that Midwestern city during his youth, and it was there as a young man he established his first animation studio. Steve sought out some of the landmarks associated with this period of early Disney history, seeking to identify places such as Walt's childhood home and the locations of the early Laugh-O-Grams Studios. Steve then very generously gave me permission to use the pictures in a post detailing the Kansas City of Walt Disney's formative years.

What began as the simple task of putting together a post showcasing Steve's efforts, quickly grew into a geographical and historical research vignette encompassing vintage photos, satellite imagery and resources such as The Animated Man by Michael Barrier and Walt in Wonderland by Russell Merritt and J. B. Kaufman. Having never been to Kansas City, I wanted to be able to better understand Walt's time there in a geographical context. I was also curious to discover just how much of Walt Disney's Kansas City had survived into the 21st century.

Michael Barrier visited Kansas City a few years back and noted, "Walt Disney's old neighborhood is so badly blighted—and so radically different from what he knew—that making that imaginative leap back to 1922 is, I'm afraid, very difficult." Barrier's observation is sadly very accurate. But despite the urban decay of the area, vestiges of Walt's life there do remain. And out of one of those vestiges, a project of both historical commemoration and neighborhood renewal may hopefully be realized some time in the near future.

Walt Disney arrived with his family in Kansas City in the spring of 1911. Their first residence was a rented house at 2706 East 31st Street, in a neighborhood a few miles southeast of downtown. For the next twelve years, the very significant events of Walt's life would transpire within a twenty-block stretch of that particular boulevard.

31st Street would form the southern border of Kansas City Star delivery route that Elias Disney would purchase that following summer. The area of route stretched north to 27th Street and was bordered on the west by Prospect Avenue and on the east by Indiana Avenue. Walt, his brother Roy, and Elias would deliver morning and Sunday newspapers to over seven hundred customers. In September of 1911, Walt enrolled at the nearby Benton Grammer School. He was required to repeat the second grade despite having completed that level while still living in Marceline. Eleven years later, he would audition students from that school for roles in Tommy Tucker's Tooth, an educational film commissioned by a local dentist. Benton student Jack Records, then eleven years old, won the part of Jimmie Jones. The school closed in 2002 and subsequently became the DA Holmes Apartments.

31st Street would form the southern border of Kansas City Star delivery route that Elias Disney would purchase that following summer. The area of route stretched north to 27th Street and was bordered on the west by Prospect Avenue and on the east by Indiana Avenue. Walt, his brother Roy, and Elias would deliver morning and Sunday newspapers to over seven hundred customers. In September of 1911, Walt enrolled at the nearby Benton Grammer School. He was required to repeat the second grade despite having completed that level while still living in Marceline. Eleven years later, he would audition students from that school for roles in Tommy Tucker's Tooth, an educational film commissioned by a local dentist. Benton student Jack Records, then eleven years old, won the part of Jimmie Jones. The school closed in 2002 and subsequently became the DA Holmes Apartments.Two blocks away from the Benton Grammer School, Walt and a childhood friend set up a pop stand at the corner 31st and Montgall during the summer of 1912. According to the friend, "It ran about three weeks and we drank up all the profits."

No trace remains of the Disney family's original Kansas City residence on 31st Street. In the fall of 1914, Elias Disney purchased a small house a few blocks east at 3028 Bellefontaine Street just off 31st Street. That home would remain in the Disney family until 1921, when Walt's oldest brother Herbert moved his family to Portland, Oregon. Elias and Flora Disney followed their son west a few months later. The house on Bellefontaine remains to this day, as does the garage that Elias Disney built sometime in 1920. It was in this garage that Walt produced the Newman Laugh-O-Grams and later Little Red Riding Hood, the first independent Laugh-O-Gram cartoon.

No trace remains of the Disney family's original Kansas City residence on 31st Street. In the fall of 1914, Elias Disney purchased a small house a few blocks east at 3028 Bellefontaine Street just off 31st Street. That home would remain in the Disney family until 1921, when Walt's oldest brother Herbert moved his family to Portland, Oregon. Elias and Flora Disney followed their son west a few months later. The house on Bellefontaine remains to this day, as does the garage that Elias Disney built sometime in 1920. It was in this garage that Walt produced the Newman Laugh-O-Grams and later Little Red Riding Hood, the first independent Laugh-O-Gram cartoon. When the house and garage at Bellefontaine became unavailable, Walt took to renting rooms and set up studios in a few different locations in an area surrounding the intersection of 31st Street and

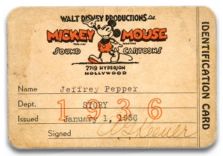

When the house and garage at Bellefontaine became unavailable, Walt took to renting rooms and set up studios in a few different locations in an area surrounding the intersection of 31st Street and Troost Avenue, about 20 blocks west of his childhood neighborhood. A now somewhat iconic design that graced an envelope shows the 3028 Bellefontaine address scratched out and replaced with a handwritten "3241 Troost," undoubtedly the first of those locations.

Troost Avenue, about 20 blocks west of his childhood neighborhood. A now somewhat iconic design that graced an envelope shows the 3028 Bellefontaine address scratched out and replaced with a handwritten "3241 Troost," undoubtedly the first of those locations.In early 1920, Walt took a job with the Kansas City Slide Company that was located at 1015 Central Street. The job paid forty dollars a week. Later that year, that company moved to a location on Charlotte Street and became the Kansas City Film Ad Company. The building on Central Street still survives in the heart of downtown Kansas City. 2249-51 Charlotte Street has since become the location of the Truman Medical Center and Children's Mercy Hospital.

In May of 1922, Walt incorporated Laugh-O-Grams Films and set up the new studio on the upper floor of the McConahy Building located at 1127 East 31st Street. The McConahy Building survives still, and has become the focus of a grass roots restoration and urban renewal effort, the details of which can be found at the website Thank You Walt Disney. Walt often took his meals at the Forest Inn Cafe on the first floor of the building, the restaurants owners frequently extending him much needed credit. It was at this location that Walt and his staff produced the Laugh-O-Grams series as well as Tommy Tuckers Tooth and the "Song-O-Reel" Martha, a live action sing-along. The Studio was just beginning production of the first Alice comedy, Alice's Wonderland in June of 1923, when a lack of rent money forced them from the building.

Some sources assert that the studio moved to the nearby Wirthman Building at the corner of 31st Street and Troost. That building was also home to the large and elaborate Isis Theater, whose resident organist was Carl Stalling. Stalling's musical talents would be employed notably and famously by Warner Bros. in Hollywood some years later. But according to Michael Barrier in The Animated Man, it is likely that Walt returned to one of his former locations at 3239 Troost Avenue. It would have been there that the studio wrapped up production on Alice's Wonderland, and Walt Disney and Laugh-O-Grams Films essentially went broke. Shortly thereafter, Walt headed for Hollywood, while former colleagues Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising and Max Maxwell launched their own studio within the walls of the Wirthman Building. Arabian Nights Cartoons would purchase and employ many of the assets and equipment of the former Laugh-O-Grams studio.

Some sources assert that the studio moved to the nearby Wirthman Building at the corner of 31st Street and Troost. That building was also home to the large and elaborate Isis Theater, whose resident organist was Carl Stalling. Stalling's musical talents would be employed notably and famously by Warner Bros. in Hollywood some years later. But according to Michael Barrier in The Animated Man, it is likely that Walt returned to one of his former locations at 3239 Troost Avenue. It would have been there that the studio wrapped up production on Alice's Wonderland, and Walt Disney and Laugh-O-Grams Films essentially went broke. Shortly thereafter, Walt headed for Hollywood, while former colleagues Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising and Max Maxwell launched their own studio within the walls of the Wirthman Building. Arabian Nights Cartoons would purchase and employ many of the assets and equipment of the former Laugh-O-Grams studio.The Wirthman Building and the Isis Theater went on to experience tragedy and adversity over the next five decades. The theater survived fires in 1928, 1939 and 1954. In March of 1970, the Isis became the center of racial unrest and rioting, and closed permanently shortly thereafter. Other tenants continued to occupy the Wirthman Building but it was ultimately demolished in 1997. A mural by Kansas City artist Alexander Austin was unveiled on the wall of an adjacent building in 2006, celebrating the history of Troost Avenue. Images of Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse are depicted on the design.