Saturday at the Archives: On Wheels of Progress

On Wheels of Progress

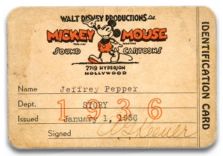

By Jeffrey Pepper

Originally published November 17, 2009

On September 29, 2006, a mere nine days into my blogging adventures, I wrote a

very brief post about one of my most favorite pieces of Disney entertainment--the generally innocuous and now considerably obscure Donald Duck film

Donald and the Wheel. I came to feel that my passion for this particular amalgamation of early xerography, rotoscoping and brief snippets of live action was a very rare emotion indeed. But I have come to discover fellow brothers in the

Wheel cause who literally span the globe. So I have decided it is time again to celebrate this largely forgotten production that continues to gather dust in an unvisited corner of the Disney celluloid archives.

Donald and the Wheel

Donald and the Wheel was in fact part of one the most dramatic transitions in the history of Disney animation--the move away from hand-inked cels to the faster and more productive xerography process. Xerography was largely the innovation of resident studio technical genius Ub Iwerks. While

101 Dalmatians is most frequently heralded as the first major demonstration of the process, it was actually used experimentally in

Sleeping Beauty, and tested more completely in the 1960 short subject

Goliath II. But largely absent from the animation history books is the further exploration of xerography in

Donald and the Wheel, which made its way into theaters a mere six months following the release of

Dalmatians. Its eighteen month production schedule certainly crossed over with those of both

Goliath II and

Dalmatians.

An exhibitor's kit for Donald and the Wheel, though steeped heavily in PR prose, provided this generally informative background on the film's technical accomplishments:

Walt Disney scores another entertainment first with his Technicolor cartoon featurette, "Donald and the Wheel." Using the revolutionary Xerox and Sodium Screen Processes together for the first time, Disney and his director, Ham Luske, combine real people and objects in the same perspective as animated characters and objects.

Walt Disney scores another entertainment first with his Technicolor cartoon featurette, "Donald and the Wheel." Using the revolutionary Xerox and Sodium Screen Processes together for the first time, Disney and his director, Ham Luske, combine real people and objects in the same perspective as animated characters and objects.

Telling the story of man's greatest invention, the wheel, required illustrations of many types of wheels and cogs, sometimes highly technical in nature. Instead of having an animator draw them, Disney had color film taken of wheels and transferred them to the screen with the Xerox Process.

For example, when a scene called for an illustration of the wheels used in a cotton gin, Eli Whitney's original invention was photographed and transferred to the screen.

With the Sodium Screen Process, Disney technicians were able to reduce a beautiful, auburn-haired ballerina to the size of Donald Duck and place her on a phonograph record with him.

The Sodium Process uses two films exposed simultaneously through the same lens, one sensitive to the Sodium screen, the other not. When the two are combined, a perfect silhouette is achieved, which is then superimposed on a master print.

The same kit provided this very detailed synopsis of the film:

In Walt Disney's newest Technicolor cartoon featurette, "Donald and the Wheel," Disney brings to the screen a story he has been working on for the past twenty years, man's greatest invention, the wheel.

The tale is told in rhyme with a pair of ghostly narrators, the Spirits of Progress, Sr., and Progress, Jr. The straight man is none other than Walt's old pal, Donald Duck, aptly arrayed in the garb of a cave man.

The faint figures of Progress, Sr. and Jr. watch a common, ordinary wheel rolling. Barrel-voiced Senior explains to bopster Junior that the wheel is man's greatest invention.

"Without the wheel, mankind would be at a standstill," he observes.

Junior disagrees. "What about the airplane, automobile, typewriter, steam engine, cotton gin, sewing machine and washing machine," says the boy.

Progress Senior strips each invention of all but its basic parts — wheels — and graphically proves his point, that the wheel, son, is man's greatest invention.

Caveman Donald, however, is harder to convince. The spirits take the little character on a meteoric ride from a circular drawing on a rock down through the ages to our present day hot rods. When Donald piles up his heap on the crowded freeways, he gives up.

Caveman Donald, however, is harder to convince. The spirits take the little character on a meteoric ride from a circular drawing on a rock down through the ages to our present day hot rods. When Donald piles up his heap on the crowded freeways, he gives up.

"Who needs wheels," he says. "I'd rather walk."

The spirits try again by showing the duck that even the world spins like a wheel, that the solar system is really wheels within wheels, that a clock depends upon wheels, gears are adaptations of wheels, and finally, a music box works on wheels.

Music is to Donald's taste, it develops, especially when a beautiful redheaded dancer does a jazz number, a square dance and a ballet with him atop of an oversized, spinning phonograph.

The spirits have chosen the wrong cave man to invent the wheel, however. Donald scurries back to his cave, erases the circle drawn in the rock and pulls his wheel-less sled over the horizon.

"No thanks," says Donald, "I'm not going to be responsible for that thing."

Senior and Junior shrug off their disappointment, but are happy that some cave man, if not Donald, eventually did have the foresight to invent the wheel.

There are likely many who negatively view the film's mishmash of rough edged styles and and distinctly non-Disney techniques and would no doubt quantify it all as short-cut animation. But in the end, director Hamilton Luske and his crew crafted a charming, entertaining endeavor that successfully mixes humor, music and education. Unlike its much more popular but decidedly stuffier cousin

Donald in Mathmagic Land,

Donald and the Wheel appropriately moves along at a much more energetic pace, largely due to the the clever rhyming dialog and equally creative song lyrics provided by Mel Leven. The song "The Principle of the Thing," whose lyrics I excerpted in

my earlier post, stands as a truly unrecognized gem from the studio's vast library of music. Thurl Ravencroft and his fellow MelloMen did justice to Leven's efforts, with Ravencroft himself performing the voice of the senior Spirit of Progress.

What is especially ironic about

Donald and the Wheel is that our favorite duck essentially plays second fiddle to the rotoscoped silhouettes of Progress Jr. and Progress Sr. A generation gap-dynamic is played out by these two characters, highlighted by Junior's beatnik-speak, again cleverly realized in Leven's rhyming dialog.

"Gazooks, Pop! This cat is really nowhere! In some circles we'd call him square"

Through narration and song, these two Spirits of Progress elevate the film beyond the potentially dry history lesson it might have been otherwise. When they are taken out of the forefront in the story's slightly weaker jukebox-phonograph sequence, the pace noticeably slows, but recovers quickly when the duo return for the final fanfare.

The short recycled animation, most notably from the Pecos Bill sequence from Melody Time, then itself later had its own material recycled for the Ward Kimball-directed 1970s' television program Mouse Factory. The gear and cog contraption created during the "Principle of the Thing" song found its way into that show's opening montage. And in an example of typical Disney synergy, the film's subject matter, humorous tone and musical nature would resurface twenty years later in the form of EPCOT Center's World of Motion pavilion.

A comic book tie-in for

Donald and the Wheel was released in 1961. It was featured in

this prior post here at 2719.