Special to 2719 Hyperion by Jim Korkis

Special to 2719 Hyperion by Jim KorkisOld time radio shows are a delight, but just like shows on television today, some were great and not to be missed, some were mediocre, and others just did not capture the potential of their concept. Unfortunately, the Disney Studios attempt at a radio show fell into the last category.

In the 1930s, radio was king and people would often change their entire lives around so that they could hear the latest episode of their favorite show. Many popular comic strip and animated characters had already made the transition to the airwaves and there were shows like “Betty Boop Fables” and “Popeye the Sailor” that entertained young audiences. Advertisers desperately wanted to sponsor a show with the Walt Disney characters and both Lever Brothers (makers of Lifebuoy among other products) and Lucky Strike cigarettes had almost convinced Walt Disney to take a chance. However, it was Pepsodent toothpaste and their commitment to a weekly budget of $10,000 to $12,000 that finally brought the Disney characters to the air in more than just occasional guest appearances on other programs.

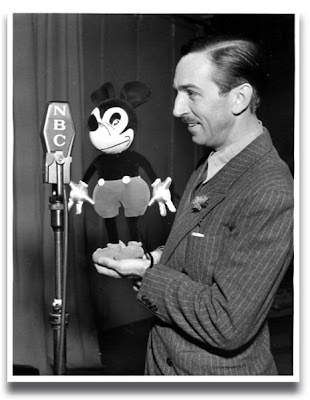

“The Mickey Mouse Theater of the Air” premiered on radio on January 2, 1938 in the NBC Sunday afternoon slot previously reserved for the antics of “Amos and Andy”. That show changed sponsors from Peposdent to Campbell Soup as well as time slots, and Pepsodent desperately wanted something as popular as those famous comedians to take up the slack.

During the half hour show, Mickey and the gang would travel through time and space thanks to the Magic Mirror from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to have adventures with everyone from Robin Hood to Cinderella to Old MacDonald. The half hour was also filled by music not just from the Felix Mills Orchestra but from Donald Duck’s Webfoot Sextet, that like the later Spike Jones Band, played a variety of odd instruments from cowbells to bottles to an auto horn for comic effect.

Here is the list of all twenty episodes of “The Mickey Mouse Theater of the Air”:

January 2, 1938: Robin Hood

January 9, 1938: Snow White Day

January 16, 1938: Donald Duck’s Band

January 23, 1938: The River Boat

January 30, 1938: Ali Baba

February 6, 1938: South of the Border

February 13, 1938: Mother Goose and Old King Cole

February 20, 1938: The Gypsy Band

February 27, 1938: Cinderella

March 6, 1938: King Neptune

March 13, 1938: The Pied Piper

March 20, 1938: Sleeping Beauty

March 27, 1938: Ancient China (with a guest appearance by Snow White!)

April 3, 1938: Mother Goose and the Old Woman in a Shoe

April 10, 1938: Long John Silver

April 17, 1938: King Arthur

April 24, 1938: Who Killed Cock Robin?

May 1, 1938: Cowboy Show

May 8, 1938: William Tell

May 15, 1938: Old MacDonald

You can listen to seven of these shows at this link.

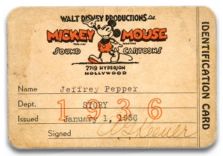

Walt himself was busy with the promotion of the just released Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and in fact, supposedly only agreed to letting his characters on the air so that it could help promote that animated feature. The reason Walt hadn’t explored radio earlier was that he felt that his characters would not translate well to the medium, that audiences needed to see as well as hear the animated stars.. Unfortunately, Walt was only able to supply the voice of Mickey Mouse for the first three episodes. From the fourth show on, the voice of Mickey was comedian Joe Twerp (yes, that was his real name) whose comedy relied on being an excitable, stuttering person who confused words. He had been considered for the role of Doc, a similar personality, from Snow White, but Roy Atwell was chosen to supply that voice instead.

Walt himself was busy with the promotion of the just released Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and in fact, supposedly only agreed to letting his characters on the air so that it could help promote that animated feature. The reason Walt hadn’t explored radio earlier was that he felt that his characters would not translate well to the medium, that audiences needed to see as well as hear the animated stars.. Unfortunately, Walt was only able to supply the voice of Mickey Mouse for the first three episodes. From the fourth show on, the voice of Mickey was comedian Joe Twerp (yes, that was his real name) whose comedy relied on being an excitable, stuttering person who confused words. He had been considered for the role of Doc, a similar personality, from Snow White, but Roy Atwell was chosen to supply that voice instead.In fact, Walt got so busy that he couldn’t attend some of the recordings and that when the script called for Walt himself to make an appearance, he was sometimes impersonated by the announcer for the show, John Hiestand!

Minnie Mouse was performed by Thelma Boardman who would later supply Minnie’s voice in the some of the Disney cartoons of the 1940s. Pinto Colvig had left the Disney Studio by the time the show started so the role of Goofy was performed by Stuart Buchanan, who was the official “casting director” at the Disney Studios and had supplied the voice of the huntsman in Snow White. Donald Duck, of course, was voiced by the one and only Clarence Nash and Clara Cluck was Florence Gill. Both of them had performed the same roles in the Disney cartoons.

There were other voices on the show as well supplied by popular performers including Billy Bletcher (the voice of Pete in the cartoons who popped up as Old King Cole in the show), Hans Conreid (still many years from voicing Captain Hook who did a comical turn as the Pied Piper), Bea Benaderet (portraying Miriam the Mermaid in the kingdom of King Neptune), Cliff Arquette (“Charley Weaver” who voiced Old MacDonald), Walter Tetley, and many others including Mel Blanc. In fact, Blanc was a regular on the show but never voiced any of the Disney characters. He did do a character in several shows that got so excited that he couldn’t stop hiccuping whenever he talked. Perhaps this performance inspired Walt to use Blanc as Gideon the cat in the upcoming production of Pinocchio. The famous story that Blanc told over the years was that he recorded a voice for the cat but Walt cut everything but a hiccup from the final performance.

The show was not memorable and suffered from the fact that Walt could not give it his full attention so it quietly disappeared after only twenty episodes but it is still an interesting footnote in Disney history. Thankfully, the estate of the musical director of the “Mickey Mouse Theater of the Air,” Felix Mills, donated all his original transcription discs of the show to the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters in California.